Workplace Culture

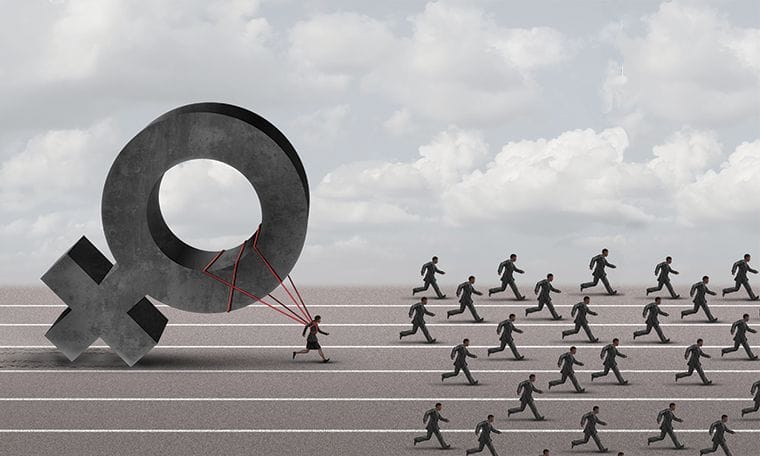

Sexism Remains an Unwelcome Advancement in the Workplace

By Rita Pyrillis

Jan. 12, 2017

When Andee Harris launched an HR tech startup nearly two decades ago she took pride in creating a workplace that supported women with family friendly benefits and ample career opportunities. She never imagined that when the company was acquired in 2011 the culture that she helped to build would change dramatically. Suddenly, she found herself unable to attend her firm’s executive retreat because it was at a male-only hunting lodge.

“Every year they did strategic planning over the weekend at a hunting lodge in Montana,” said Harris, 43, who was chief marketing officer at the time and the only woman on the executive team. “For 10 years it wasn’t an issue and then I joined the team. My CEO said, ‘We just realized that they don’t allow women so we’ll just take notes and follow up with you.’ I said, ‘No, I’m going to go.’ ”

The CEO called the lodge and convinced them to make an exception, but according to Harris the damage was done. She resigned soon after.

“They weren’t trying to be mean about it, but they didn’t realize the position that they put me in,” said Harris, who is now chief engagement officer at HighGround, a Chicago-based tech firm. “I pushed back and accused them of being sexist, but in their eyes they accommodated me. In tech, sexism is not as blatant as some women think it is. It’s not ‘grab ’em by the pussy.’ It’s a lot of little things that add up.”

Harris was referring to comments made in 2005 by newly elected President Donald Trump that were caught on a videotape uncovered by the Washington Post in October of last year. Trump, then a private citizen, can be heard boasting about kissing and grabbing women by the genitals.

Most sexual discrimination in the workplace is much more subtle than blatant harassment and takes many forms, according to Rosalind Barnett, a researcher at the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University. While sexual discrimination in hiring, pay and other aspects of employment is illegal, attitudes and certain behaviors are much harder to prove. Sexism can mean being denied a promotion in favor of man who is deemed a better cultural fit, being talked over in meetings or never getting credit for your ideas, she said.

“Gender discrimination hasn’t gone away, its gone underground,” said Barnett, who coauthored the 2013 book “The New Soft War on Women: How the Myth of Female Ascendance is Hurting Women, Men, and Our Economy.” “We’re talking about things that are not legally actionable. People who do this are often not even aware of it. Sexism is in the air.”

While Trump’s comments were roundly condemned, some brushed them off as “locker room talk,” which women’s rights advocates see as a tacit acceptance of sexist behavior, including harassment. Many fear that workplace sexism could get worse.

“[November’s presidential] election threw so many of us for a loop,” said Meg Bond, psychology professor and director of the Center for Women & Work at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. “You realize that there are people who are not bothered by deep sexism and racism and that’s disturbing. Are we are bracing for more sexism in the workplace? Absolutely.”

Bond is a member of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s special task force on the study of workplace harassment, which released a lengthy report in November showing that it remains a big problem. In 2015, the EEOC received 28,642 sexual harassment complaints, representing nearly one-third of the all complaints filed that year. That averages to 76 complaints a day, according to the report.

Defining Discrimination

Sexual harassment is a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination based on national origin, sex and religion. The most common type of sexual harassment is called quid pro quo harassment and involves demanding sexual favors in exchange for some kind of employment benefit, according to Tom H. Luetkemeyer, an attorney with Hinshaw & Culbertson in Chicago. The other kind is hostile environment harassment, which is defined as “frequent or pervasive” unwanted sexual advances or comments that create a hostile workplace, he said. Harassment also includes making offensive remarks about a person’s sex — whether female or male — or being subjected regularly to offensive jokes or images.

“If it’s severe and objectionable on an objective and subjective basis and it’s based on gender, it will likely rise to the level of sexual harassment,” Luetkemeyer said.

And if left unchecked, employers could ultimately pay a big price.

In 2015, the EEOC settled 5,518 sexual harassment cases totaling $125.5 million. Since 2010, employers have paid out $698.7 million to employees alleging harassment through the EEOC’s administrative enforcement pre-litigation process alone, according to the report.

In addition to legal expenses, employers who fail to address sexual harassment are likely to see a decline in productivity and higher health care costs, according to Bond. Workers who experience sexual harassment often suffer depression, anxiety, turnover, more sick days and a host of physical ailments that come with psychological distress, she said.

“Women who work in an environment where there’s harassment are less happy, and men are also less satisfied,” Bond said. “It’s not just a few targets that are victims. It’s the whole workplace.”

Yet, only 30 percent of employees who experience sexual harassment report it to their employer, according the EEOC report. Most try to avoid the harasser, deny or downplay the incident, or try to live with it, the report found.

HR’s Harassment Role

That is not surprising to Michelle Phillips, an employment attorney with Jackson Lewis. She questions whether HR is the right place for victims to go to lodge a complaint. She said that women may feel unsafe telling their stories to employees who may have been hired by the executives accused of the harassment.

“HR professionals play a critical role in a company’s culture, so it’s important for them to set the standard and be part of the enforcement mechanism to make sure complaints are heard and that no retaliation occurs,” she said. “The number one reason employees don’t report harassment is retaliation. They are afraid of being fired, shunned, ignored or intimidated. Like with Roger Ailes, a company can have a culture of not reporting things. HR plays a critical role in that.”

Please also read: Building a Sexism-Free Workplace

In July, Fox News CEO Ailes resigned amid accusations that he sexually harassed current and former female employees throughout his career. The scandal left many observers wondering how he was able to do this unchecked for so long.

Liz Washko, an employment attorney with Ogletree Deakins, advises employers to provide multiple ways for employees to report harassment or other types of sexual discrimination, such as a hotline and one or two HR representatives to hear complaints. But most importantly, she urges employers to follow through.

“You can have best policies but if you don’t act it means nothing,” she said. “We recommend that employers take complaints seriously and investigate them, and if they conclude there is an issue, then take corrective action.”

Claiming ignorance doesn’t protect employers from liability, according to Washko.

“I would urge vigilance right now,” she said. “People might not come to you. Make sure that front-line managers understand the importance of protecting employees and ask them to keep their ears to the ground so that maybe they can alert you. Even if people don’t complain, the company could be liable if these things are happening in the workplace.”

Identifying the Disconnect

The first step is learning how to spot sexist behavior, according to Valerie Aurora, CEO of Frame Shift Consulting, a San Francisco-based tech diversity and inclusion firm. This is especially challenging in tech where sexist attitudes are common, even though the industry prides itself on its progressive culture.

Aurora started Frame Shift last year to help companies address this disconnect. One of the services that Aurora offers are ally skills workshops, training that teaches people how to use their societal privilege, like being white, or male, or wealthy, to help others. She said she developed the program in 2011 after a friend was groped at an open source software conference.

“I think our self-image as an industry and our actions are out of sync,” she said. “A lot of us think sexism is bad but a lot of us are acting in sexist ways.”

While many companies believe that sexual harassment training is the key to tackling the problem, she said most approaches are ineffective.

“Many times the instructors are rolling their eyes and telling people that they don’t want to be there, that they’re forced to do this legally, so no one takes it seriously,” she said. “You watch a 10-minute video and go home thinking, that was pointless.”

A better approach is to help people walk in someone else’s shoes in order to make them aware of their own subtle biases. Ally skills workshops focus on real-life scenarios to drive the point home.

“For example, you’re in a meeting and a woman has an idea and everyone ignores it and 30 minutes later a man voices the same idea and everyone gives him credit,” she said. “What can you do to make sure that first person gets the credit?”

Harris agreed that having allies in the workplace who are willing to speak out against instances of sex discrimination is key to creating a civil workplace. But she also encourages women to speak up for themselves.

“We need people who will have your back — whether they are men or women,” she said. “As women we tend not to fight and we sometimes let people take credit for our work. I think it’s also important that women stand up. Many companies focus on diversity and inclusion, however, a lot of companies don’t even realize how biased they really are.”

The workplace has become the front lines in the battle against all forms of discrimination, and employers have a responsibility to address them, according to Bond.

“The workplace is one of the primary places where people can and often do come into contact with people of different views,” she said. “It is an important setting for increasing understanding and equity. Some employers do see that they can play an important role in our society by helping to bring people together across differences.”

Rita Pyrillis is a writer in the Chicago area. Comment below or email editors@workforce.com.

Schedule, engage, and pay your staff in one system with Workforce.com.