Workplace Culture

Return From Rehab: Dealing with Demons and Deadlines

By Kate Everson

Mar. 23, 2015

Dr. Julie Colby’s colleague found her unconscious on a table at a Massachusetts hospital in July 2004. The anesthesiologist had self-administered fentanyl — one of the same drugs she used on patients to ease post-surgery pain — which she had been doing until she became addicted to the powerful opioid.

Colby lost her medical license but won a court case in 2013 that expanded rights for workers coming out of substance addiction rehabilitation. In Colby v. Union Security Insurance Co., the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston declared that employees who had been in rehabilitation were eligible for long-term disability if they felt their place of employment contributed to their addiction. In Colby’s case, administering fentanyl as an anesthesiologist had led her to self-medicate and become dependent on the narcotic, the court ruled.

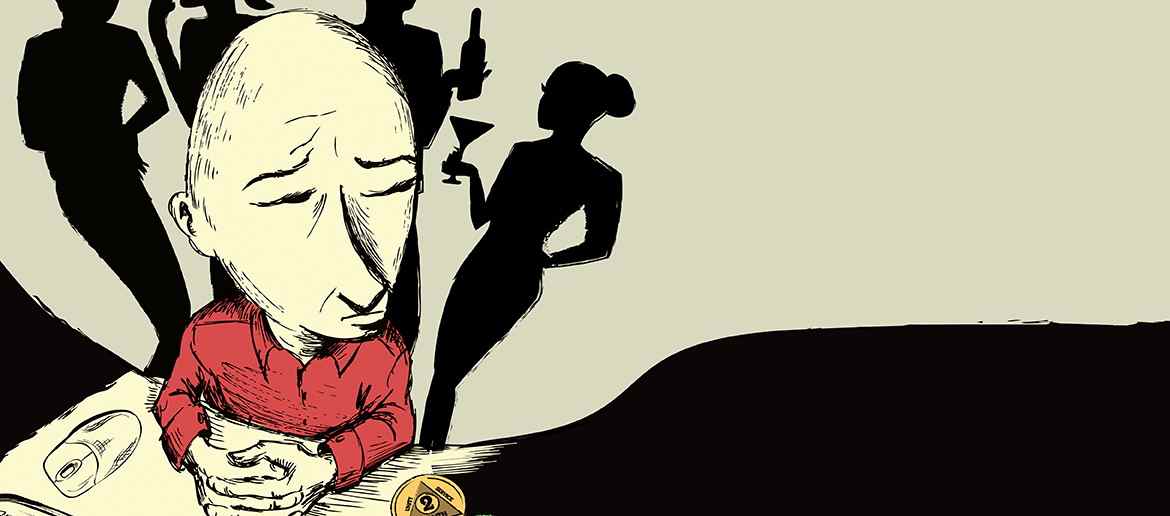

Most drug and alcohol addictions can’t be legally blamed on the workplace. That means many employees coming out of rehabilitation will return to work once their program ends. Though crucial for an employee on the road to recovery, going back into the workplace can also be a stressful, difficult process.

“It’s a whole lifestyle change,” said Sally Littell, manager of Back on Track, a Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania-based employee assistance program. “Imagine yourself changing friends, the relationship with your family, where you hang out — it’s everything.”

More than 40 million, or 16 percent of Americans age 12 or older, meet the clinical criteria of having a substance addiction to alcohol, nicotine or other drugs, according to a 2012 report from the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University titled “Addiction Medicine: Closing the Gap Between Science and Practice.” However, only 1 in 10 of those addicted to alcohol or non-nicotine drugs receives any kind of treatment.

But the few who do enter rehab also have to deal with the reality of returning from it. Amid the lifestyle changes, the workplace can be among the few stable environments that carry over from before treatment. The human resources department can be a post-rehab employee’s best resource. Being that ally means understanding an employee’s needs, compliance with legalities and developing a cooperative workforce.

You Have the Right to Remain Employed

Workers returning from a substance-abuse program are often unaware of their rights, said Dr. David Sack, president and CEO of Elements Behavioral Health at California’s Promises Treatment Centers. He said HR should educate returning workers on the Americans with Disabilities Act, which covers substance abuse, and what it means for their job security.

Most state and federal laws require employees to be fit for duty before returning to work. As long as their doctors declare them ready for release, they can come back without being questioned by their managers as to where and why they were gone. Employers are also required to comply with any special limitations a health care provider deems necessary for recovery, such as time off for doctor appointments and introductory limits on work hours.

The time to discuss these rights comes hand-in-hand with another post-rehab procedure: a return-to-work meeting. It might sound inviting, but Littell said it can actually be intimidating for everyone involved.

“The HR people are probably as nervous about it as the patient because it’s not something they do all the time,” she said. “Put on a different lens. Pretend the person across the table from you is coming back from a heart attack.”

Composing a Return-to-Work Agreement

Rather than use a cookie-cutter list of restrictions,human resources representatives have to collaborate with an employee and the employee’s health care provider or rehab center to tailor a return-to-work agreement that focuses on the worker’s post-rehabilitation. JonathanSegal, a partner with law firm Duane Morris, said these are pivotal questions to ask when composing the agreement:

1. Are there any restrictions that apply when the employee returns to work?

2. Do you recommend the employee continues treatment? If yes, how long?

3. Do you recommend we monitor the employee’s treatment? If yes, how long?

4. Do you recommend there be periodic testing? If yes, how often and how long?

5. Do you recommend the person should be required to refrain from any use of alcohol or drugs, even off-duty?

—Kate Everson

Littell said this change in mindset makes it easier to ask questions like “How are you?” “What can we do to make this more comfortable for you?” and “What accommodations do you need us to make?” A free-flowing conversation is pivotal to drawing up a return-to-work agreement, which outlines the rules and parameters that have to be followed by an employee coming back to the office.

Jonathan Segal, a partner with law firm Duane Morris, said the key is to make sure the return-to-work agreement is individualized and set up primarily by the rehab center. These would outline continued treatment plans, whether an employee will be subject to periodic testing and any restrictions regarding that employee’s return to work, such as how much time the person is allowed to be on the job.

It might also include requirements to refrain from any use of drugs or alcohol, both on-and off-duty — an area of the law that gets complicated, Segal said. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission wrote an informal opinion letter in August 2014 saying that restricting a recovering alcoholic worker from drinking subjects that employee to a higher standard than the person’s nonalcoholic peers.

“There is at least one case out there that arguably supports it, but, on the other hand, it seems to ignore the reality that the individual is in a different situation,” Segal said. “To say that someone who is recovering from alcoholism isn’t prohibited from drinking, and then you allow that person to return to work and operate on someone, or operate a forklift, may result in deaths.”

Any employee who comes to work impaired can make a serious mistake that costs the company money or potentially employees’ lives, but someone who has gone through treatment runs the risk of a relapse, he said. Return-to-work agreements act not only as an incentive for employees not to relapse but also a way for companies to discipline workers if they do come to work impaired despite having gone through treatment.

Employees whose addictions have already caused problems on the job might come back on a last-chance agreement, which often requires a lawyer’s services, Segal said. These contracts state that employees have to follow the work rules and perform the essential functions of their position, and another problem related to an employee’s addiction will be met with discipline, which could include termination.

As punitive as such a contract sounds, Littell said it can help an employee continue recovering. People coming out of substance-abuse treatment need every reason they could possibly have not to start using again, and the salary, health benefits and personal dignity that come from a job are three more reasons to maintain sobriety, she said.

The law also comes into play to regulate communication, a difficult task when determining who is privy to the details of an employee’s leave.

“It depends on the culture,” said Lisa Orndorff, manager of employee relations and engagement for the Society for Human Resource Management. “At some places, everyone in the hierarchy wants to know all the ins and outs because they don’t know there are certain restrictions on what they can and need to know. You get to do a little HR lesson with them at that point.”

There are only two things supervisors need to know, Orndorff said: that an employee is out on Family and Medical Leave Act leave and the worker’s anticipated return date.

Orndorff said SHRM’s policy lets a post-rehabilitation employee know which managers are aware of the worker’s absence under FMLA, which helps calm fears of who knows and how much they know.

If employees don’t want to share where they’ve been — something they’re not obligated to divulge — HR can help them craft the wording so that their explanation is comfortable for them but doesn’t invite more questions.

“It helps them think through how to answer the question when it comes up, because it will come up,” Sack said. “Maybe they say something like, ‘I don’t want to talk about it, but I’m grateful to be back at work.’ Sometimes you just choose deflection and gratitude, and it’s very hard for other people to take issue with that.”

Managing the Rumor Mill

Confidentiality is legally required, but shrouding a worker’s absence in silence triggers speculation from co-workers, which can turn to suspicion.

“The rumor mill gets started early, and it doesn’t take much to fan that fire,” Orndorff said. It’s up to HR to take the necessary steps to keep human nature from getting in the way of a returning employees’ reintegration into the workplace, she said.

Orndorff has worked with managers at midsize companies to help them stay in tune with what’s being said and felt around the office regarding an employee on leave or newly returned. Supervisors are the ones maintaining communication with employees before, during and after a worker comes back from rehab, and HR can help with that.

Of course, rumors can start up even before an employee leaves for rehab, let alone when that person returns, Orndorff said. Peers are perceptive of each other, and performance issues or behavior based on addiction can raise flags within a department even before a manager notices. The flags won’t be lowered while an employee is gone either.

“Help managers take responsibility for the situation,” she said. “This is not one of those things where if you ignore it, it will go away. Keep an open line of communication.”

But sometimes the best defense comes before there’s even a post-rehab return.

“Most workplaces don’t want to acknowledge that these are issues,” Sack said. “Addictions are the uncle in the attic — they don’t want to acknowledge them because they’re afraid they’ll invite them somehow.”

Instead, HR has the opportunity to spearhead initiatives that teach employees about addictions, regardless of whether there’s an actual case of it at work. He said negative reactions against people who are out for rehab stem from the social prejudice that addiction is a controllable personality flaw rather than an illness.

Sack said hanging these perceptions of addiction starts with education, particularly teaching that addictions are medical disorders with genetic triggers and are treatable.

Online training systems are available that aim to help supervisors become more knowledgeable on substance abuse and ADA rules, Sack said. Focusing on the facts behind addiction can halt rumors and make the work environment a more welcoming place for someone after rehab, he said. Organizations can also include it in their employee handbooks.

Putting the rumor mill and legalities to rest can allow employees to focus more on their contribution to the organization. People battling addiction need little victories as well as big ones to keep them on the road to recovery, Littell said.

But this doesn’t mean treating employees as fragile beings at risk of cracking at a moment’s notice. Tip-toeing around returning employees actually hampers their reintroduction to the workplace. Sack recommended that HR work with management to break the ice by bringing an absent employee up to date on what that person’s missed while gone and educating the worker on any procedural changes that might have occurred.

Eliminating these obstacles from the beginning gets employees in step with their peers, which can improve the morale of a department that’s been one worker short for an extended amount of time — something that can be critical depending on an organization’s culture and interdepartmental relationships, Orndorff said.

If a person is doing good work, they begin to regain confidence, Sack said. If post-rehabilitation employees aren’t performing up to speed, HR can encourage managers to give feedback with the angle of getting them on track faster. It helps the employee know where they stand and keeps supervisors from getting frustrated.

“An HR manager can be very helpful in educating and helping supervisors to make an appropriate plan,” Sack said. “So many problems can be prevented when a supervisor meets with an employee to give feedback. What that does is it ensures an employee that they’re on the right track, that a supervisor cares about them, that their work is respected. And that’s really important.”

Schedule, engage, and pay your staff in one system with Workforce.com.